New study estimates how many children will get long Covid

An international study estimates the prevalence of long Covid in children to be anywhere from 5% to 10% — a figure that's far lower than estimates of long Covid in more than a third of adults.

An international study estimates the prevalence of long Covid in children to be anywhere from 5% to 10% — a figure that's far lower than estimates of long Covid in more than a third of adults.

The findings, published Friday in the journal JAMA Network Open, also suggested that several factors could predict which children with Covid may have ongoing symptoms or develop new ones in the 90 days following infection.

Those include having seven or more symptoms during the initial phase of illness and hospitalization for more than two days. Age was also a factor: Long-term symptoms were more prevalent in children 14 years and older.

Full coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic

"This identifies those children that we need to stay in closer touch with" as they recover following a positive Covid test, said study co-author Dr. Nathan Kuppermann, a professor in the department of emergency medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine.

In the study, Kuppermann and a team of researchers interviewed parents and their children who had been taken to the emergency room for Covid. Interviews were conducted two weeks and then three months after the emergency room visit. Study participants came from eight countries: Argentina, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain and the United States. The majority were from the U.S.

The project included 1,884 children diagnosed with Covid and seen in an emergency department from March 2020 through late January 2021, as well as 1,701 children without Covid, but who sought urgent care for other reasons.

Nearly 1 in 10, or 9.8%, of children who were sick enough with Covid to be admitted to the hospital reported ongoing symptoms — often fatigue, cough and shortness of breath — three months later.

Among Covid-positive kids sent home directly from the ER, 4.6% continued to have symptoms 90 days later, the report found.

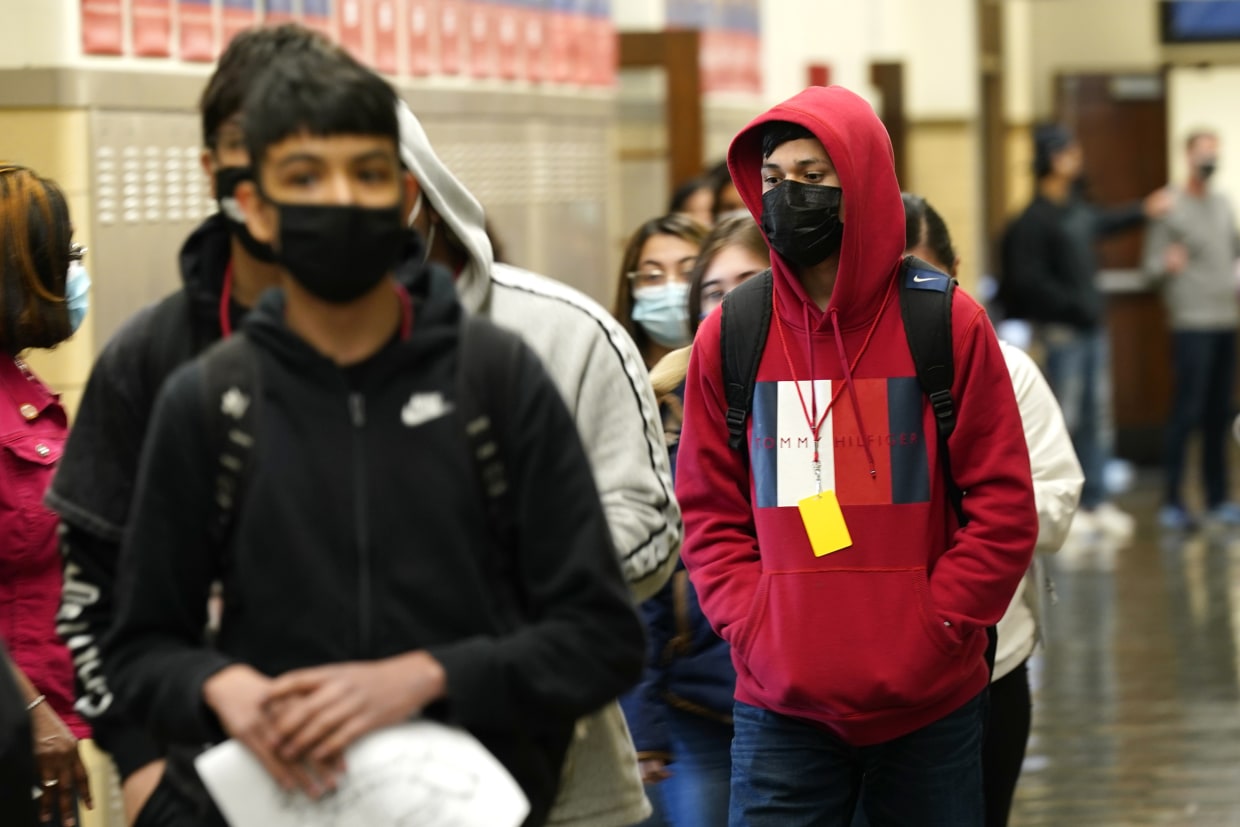

The number of children testing positive for Covid has been rising in recent months. More than 75,000 new pediatric cases were reported the week ending July 14, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. That’s an increase from 68,000 reported cases the week before.

The study's estimates of about 5% to 10% of kids with long Covid line up with what pediatric infectious disease experts are seeing in their clinics, said Dr. Roberta DeBiasi, chief of infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital in Washington.

The message to parents, she said, should be one of reassurance.

"The odds are on your side that if your child gets Covid, it’s going to be a mild illness," DeBiasi said, "and they're not going to have long-term symptoms."

There are several theories as to why older teens may be more likely than young children to have long-term symptoms. It could be, Kuppermann suggested, that adolescents have more viral particles in their system upon infection.

It is more likely, however, that teenagers are simply better at expressing what they're feeling.

"We're relying on parents to report how their kids are acting," Kuppermann said. "A 2-year-old isn't going to tell you about Covid fog, and I'm not sure their parent would be able to detect Covid fog in a way that maybe a 15-year-old could."

The research also found that as many as 5% of kids in the hospital for reasons other than Covid also had ongoing symptoms, such as fatigue, trouble concentrating or even abdominal pain, 90 days later.

This suggests that perhaps other factors related to the pandemic — lockdown, isolation, remote schooling — may also play a role in ongoing symptoms.

"So much has been going on at the same time in the lives of adolescents," Kuppermann said. "They've been isolated from their friends. They've not been in school."

"The effects of the Covid era include not only Covid infection, but substantial increases in mental health issues," he said.

Persistent symptoms that include fatigue and trouble concentrating in children are worthy of a doctors' care, DeBiasi said, regardless of whether the cause is Covid or something else.

"Not thinking clearly, having difficulty in school because of that, anxiety, depression — there's a variety of things we're seeing," she said.

"We want to make sure they get the care they need and not feel dismissed," DeBiasi said. "We don't want these kids to suffer."